There is something uncomfortable about the Battle of Vega

Real. If one accepts the accounts of Bartolomé de las

Casas and Ferdinand Columbus, it should be listed as the first major

battle between Europeans and Indigenous Americans, with the victory going to

the former while sending the latter into ignominious defeat and wretched

subservience. Yet the nearly mythological descriptions of the battle, with two hundred twenty Spaniards defeating a hundred

thousand Tainos seems so exaggerated as to make one wonder if it is even

possible to discover what really happened on the plain of Vega Real in March

1495. The fact Columbus had twenty

men on horse, twenty dogs, and European weapons hardly seems enough to overcome

the odds, unless one assumes, as las Casas and F. Columbus both do, that

there was some aboriginal incomprehension about what they were encountering in

arms, animals, and men, some cowardice bred of the shock of the unknown that

infected an immense gathering of people who had come from all over the island

of Hispaniola and confounded their ability to respond effectively.

In response to my article about the dogs Columbus used at

the Battle of Vega Real, I received some emails from readers who questioned why

they had not heard more the battle itself, let alone the horses and dogs that

seemed a factor in the Spanish victory. “A battle that supposedly involved 100,000

indigenous men in 1495 would seem to have been a very important battle. Why haven’t I heard of it?” Something of the

same question was in the back of my mind from the very beginning of my research

into the battle. Let me see if I can add some perspective to this very valid

question.

What Did Warfare Mean to the Indigenous of Hispaniola?

Given that the Battle of Vega Real was one of the first

military encounters between the Indigenous and the Spanish, we must consider

what warfare meant to the Indigenous of Hispaniola in 1495. Herrera’s frontispiece, reproduced in the prior blog and my article,

portrays two armies at the beginning of a field battle, each on one side of the

battlefield, weapons raised, dogs being released, cavalry entering from the

side. Would the forces gathered by Caonabo or his brother be organized this

way, as if they fought under the same rules of engagement as a European army?

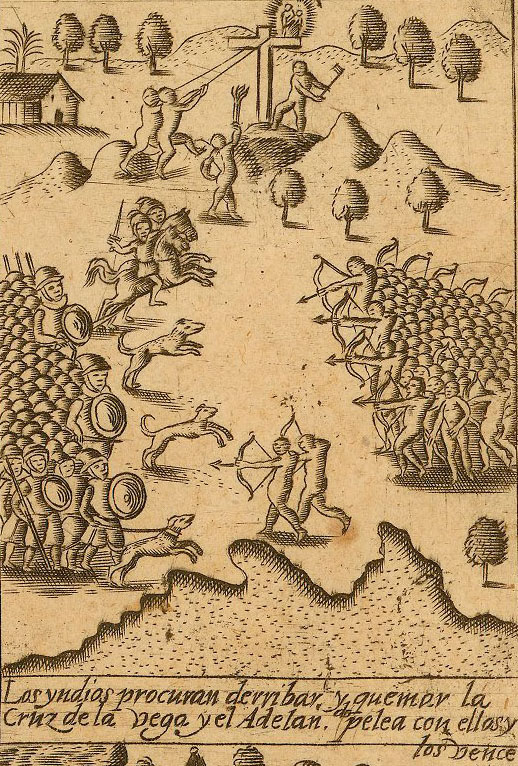

The illustrator of the frontispiece of the 1601

edition of Herrera’s Historia natural does show another encounter where there was not such a structure to a battle, the attack on

Navidad when Columbus was back in Spain after his first voyage. In fact, the illustrator includes two separate panels, one showing the fortress before Columbus left Hispaniola, and one showing it under attack as he returns on his second voyage (the destruction of Navidad and Columbus's return were not simultaneous but the inclusion of ships of the return fleet made the composition more dramatic). See Figure

1.

|

|

Figure 1. Two panels from Historia general, Herrera y

Tordesillas 1601, showing (left) the founding of Navidad and (right) its

destruction. The left caption translates: The Admiral says goodbye to King

Guacanagari, building La Navidad. The wrecked Santa Maria, from whose timbers

the fortress of Navidad was built, is shown partially sunken in the water

beside the fortress. Guacanagari, who

controlled the area of the construction, is being carried by his subjects while

Columbus surveys the area. The right

caption translates: The Admiral returned and found the tower of Navidad burned

and the Castilians murdered. The Indigenous are shown attacking with arrows and

fire.

|

As to the Battle of Vega Real in 1495, Ferdinand Columbus states that his father, understanding the

Indigenous character and habits, intended to attack the diverse multitude

scattered throughout the countryside, assaltar da diverse parti quella

moltitudine, sparsa per le campagne (Historie del S.D. Fernando Colombo,

1571, 123; Columbus and Keen 1984, 149, whose translation is less of a literal

transliteration than mine). Figueredo

(2006) describes the Tainos as giving battle “guided by strategic designs that

demanded rigid organization.” Yet Caribbean warfare was also said to be

“noisy and showy with skirmishes lasting entire days” where “a melee of

personal insults, challenges and combats was the norm” (Glazier 1978).

Thus, an alternative conception of the encounter at Vega Real might be that the Indigenous gathering on the plain did not array themselves against

the forces of Columbus, perhaps expecting a period of shouting and threats before arms were picked up. Perhaps they thought their overwhelming numbers would demonstrate their

resolve and force Columbus to retreat. Or perhaps many of them were just in their

houses and going about their lives, as they had at other times that Columbus

and his subordinates had marched through Vega Real.

Were There Military Encounters Between Europeans and

Indigenous in 1494 Before the Battle of Vega Real?

It has already been mentioned that when Columbus returned to Hispaniola in his second voyage, he found that Navidad had been destroyed and the men he left there had been killed. He was told that some of the Spaniards had fought and killed each other and the rest had been killed by the cacique Caonabo (Las Casas 1875, vol. 2, lib. 1, cap. 86, 13; Columbus and Keen 1984, 119), who would continue to be the primary Taino leader opposing Columbus during the second voyage.

Ferdinand Columbus records what appear to have been

relatively minor skirmishes in 1494 around the fortresses built for gold mining

operations (Columbus and Keen 1984, 129; Wilson 1990, “The First Skirmishes," 82-84). See

Figure 2, showing how the Indigenous were supposed to happily engage in mining and panning gold for the Spanish. They were not, however, particularly happy and manifested their displeasure quickly. An attack on the fortress at Magdelena in late 1494 brought a response that resulted in the

capture of 1,600 Indigenous in the Macoris area, 550 of whom were sent to Spain as

slaves in caravels that departed from Hispaniola on February 17, 1495 (Morison

1963, 226, translating the letter of Michele de Cuneo; Anderson-Cordova 2017, 31). Thus, there was a period where Spanish groups

building fortresses were attacked, but the resistance seems to have been rapid,

spontaneous, and not the collective effort of a group of caciques, as may have happened in March 1495.

|

|

Figure 2. Oviedo y Valdés, Historia general, recto of leaf 66, Indigenous mining and

panning for gold. JCB Accession No. 01632, Juan de Junta, 1547, Salamanca.

|

Was the Taino Force at Vega Much Less than 100,000, Say Just 5,000?

The number of Indigenous fighters that Columbus encountered at Vega Real,

said to be 100,000 by both Las Casas and F. Columbus, is often doubted

and sometimes even summarily rejected. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549-1625),

writing about a century after the battle, takes the number given by the earlier

sources, but rather than simply repeating that there were 100,000 Indigenous on

the plain, he hedges, saying that the natives seemed to amount to one

hundred thousand, todo el parecio ser de cien mil hombres (Historia

general, vol. 1, Decada I, lib. 2, cap. 17, 77; Parry and Keith 1984, 201).

This suggests that a sixteenth-century historian was already uncomfortable with the size

that Las Casas and F. Columbus had given the Taino force.

Kathleen Deagan and José María Cruxent (2002, 61), in their

brilliant description of the settlement at La Isabela, state that the Taino

caciques organized an insurrection, “allegedly planning to march against La

Isabela with a force more than five thousand strong,” thus ignoring the number

of combatants given by Las Casas, F. Columbus, and, grudgingly, Herrera.

A footnote in their book indicates that they have taken the more credible

number from Pietro Martire d’Anghiera’s De Orbe Novo (Parry and Keith,

1984, 208-210), which describes the force encountered in the Cibao by Alonso de

Ojeda as “about 5000 men [cinco mil hombres armados á su manera],

equipped in their fashion, that is to say, naked, armed with arrows without

iron points, clubs, and spears.” (There is probably a textual error in the 1892

edition of Martire, Fuentes historicas sobre Colon y América, which

reads, at 221, unos mil armadas instead of unos cinco mil armados).

Martire’s description of Ojeda does not

mention the Battle of Vega Real but I do believe Deagan and Cruxent have

correctly correlated the passage in Martire with events that were either part

of the Battle of Vega Real or that followed immediately after it, but I

would have liked to see further comment on this substitution of numbers. Shoring up the

accounts of Las Casas and F. Columbus by finding correlations in the accounts

of early chroniclers of the conquest who do

not specifically mention a battle at Vega Real produces a more

credible description of the battle, but such jerry rigging simultaneously demonstrates

that there is no single early account that is entirely credible. This, among

other reasons that will be discussed below, probably results in historians

shying away from paying too much attention Vega Real and makes some of them reluctant to anoint the battle as the first major

conflict between Europeans and the Indigenous.

Was the Population of Hispaniola Sufficient for an Army

of 100,000 Indigenous Even to Be Possible?

Before accepting the reduced size of Columbus’s opponents at

Vega Real, it might be appropriate to ask whether it would have even been

possible for any group of caciques to gather 100,000 people at the Vega Real in

1495. Michele de Cuneo, in a letter written in 1494, wrote that the cacique Caonabo could

field 50,000 men (Parry and Keith 1984, 89, translating from the Italian, homini

L mila; Cuneo, Lettera [1495] 1893, 99), although this reference is not

mentioned in connection with a specific battle.

A preliminary question concerns whether the population of

the island in 1495 was sufficient for such a sizeable force to be

possible. One of the first

anthropologists to estimate populations of the Caribbean was Alfred Kroeber

(1934), who placed the population of the West Indies at 200,000, meaning the

population of Hispaniola could not have fielded a force of 100,000. Angel Rosenblat (1967) put the

population of Hispaniola in 1492 at between 100,000 and 120,000, also too small.

Kroeber was attacked for his estimates. Francis Jennings

(1975, 18-19) described him as a “dissident scholar” who “emphatically

rejected the notion that the natives of North America could be considered

capable of so ordering their societies and technologies as to increase their

populations beyond a static and sparsely distributed token representation.”

William Denevan (1996) said that Kroeber’s estimates were the result of

“antithetical conceptions of the quality and capacity of aboriginal cultures

everywhere in the Americas.”

Tink Tinker and Mark Freeland (2008) estimated that the

population of Hispaniola in 1492 was just shy of eight million (7,975,000 to be

precise) but accepted that Las Casas was correct in arguing for a precipitous

decline under early Spanish rule, going down to 3,770,000 by 1496, with only

500,000 surviving by 1500 and 60,000 by 1507.

Their numbers thus allow for fielding a considerable force in 1495, but probably not a few years later.

Samuel Wilson (1997) finds the number 100,000 implausible,

though he accepts that 15,000 men could have been raised in 1497 (Stone 1990,

97-102). He makes the important observation that famine and epidemics had even

five years after contact considerably reduced the population of the island.

As I noted in my paper, recent genetics research (Fernandes

et al. 2020) has estimated that the pre-contact population of Hispaniola and

Puerto Rico combined could have been at most 80,000 people. Various assumptions are made in the calculation of population sizes using genetic

analysis, but if this research is upheld, a lower number than some of those

proposed will likely have to be accepted and the estimates of Kroeber and

Rosenblat may be judged not so far off after all.

If Las Casas and F. Columbus Exaggerated the Number of

Indigenous at Vega Real, Why Did They Do So?

Juan Friede and Benjamin Keen (1971) summarize some of the

reasons for exaggeration of population estimates in sixteenth-century accounts

(I add numerals in brackets):

[1] The conquistadors wished to

stress the heroism of their feats; [2] the clergy sought to enhance the

importance of their missionary and evangelizing work; [3] pro-Indian

polemicists wished to present a somber picture of the activities of the

conquistadors; [4] enthusiasts of the Indians’ past were eager to idealize or

hyperbolically exalt that past; and [5] obsessive Hispanophiles wanted to

present the Indian as a biologically and culturally inferior being.

Las Casas could have exaggerated for reasons (2) and (3), F.

Columbus for (1), and modern commentators who uncritically accept the numbers

of earlier accounts may belong in (3) through (5), though laziness in questioning

earlier accounts may not implicate any serious bias due to any of these

reasons.

How Many Allies Did Columbus Bring to Vega Real?

Two hundred twenty men against 5,000, accepting an

adjustment to the numbers of Las Casas and F. Columbus, is still a significant

discrepancy and it would seem that even a terrified mass of 5,000 Indigenous

fighters could get off enough arrows to finish off a few hundred men, horses,

and dogs. As I mentioned in my paper,

the size of Guacanagari’s force allied with Columbus becomes, therefore, a

significant factor. F. Columbus assigns no number to the allied force, saying only that Guacanagari

was eager to oppress his enemies, Guacaanagari molto disderoso di opprimere

I suoi nimici (F. Columbus, Historie del S.D.

Fernando Colombo, 1571, 123; Columbus and Keen 1992, 148). Las Casas realizes that

the size of Guacanagari’s force would be relevant, but parenthetically

apologizes that he could not find the number of his vassals, (no pude saber

qué gente llevó de Guerra, de sus vasallos). (Las Casas, 1875, vol. 2, lib.

1, cap. 104, 97).

Here again, some creativity is required to estimate the size

of Guacanagari’s contribution in men. I noted in my paper that Erin Stone

(2021) takes the number of 3,000, citing Sauer (1966, 89, who only refers to

"Guacanagari of Marien and his men"). The number is, however, quite credible as it is used

by Martire for the indigenous allied force later used by Bartolomé Columbus

against Guarionex (1892, vol. 1, Decada 1, lib. 7, cap. 1, p. 284).

Who Led the Indigenous Forces against Columbus at Vega

Real?

The frontispiece panel of the 1601 edition of Antonio de

Herrera’s Historia general depicts

Columbus facing Guarionex, their respective armies behind them. Were the Battle of Vega Real such a clearcut

European-style engagement, one would expect accounts to identify the two commanding

generals that faced each other in March 1495.

This is not the case, however, and it is doubtful that we can ever be

certain who led the Indigenous forces, or whether they were even under the

command of a single individual.

Las Casas does not specifically name a commander for the

Indigenous forces, though in the chapter that describes the battle he does

refer to Guatiguana, Cacique of Magdelana, who had earlier killed ten Spaniards,

10 cristianos (Las Casas, 1875, vol. 2, lib. 1, cap. 104, 98). Wilson (1990, 89-90) notes that Samuel Eliot Morison,

in Admiral of the Ocean Sea, preferred Guatiguaná as the leader of the

resistance, a possibility Wilson does not reject though he also accepts the

possibility that the leaders were “notorious and nameless brothers of Caonabo.”

The latter would be the current author’s choice, should he be entitled to have an

opinion on this. Wilson, correctly in my

opinion, states that although Guarionex is “consistently considered by all of

the chroniclers to have been the most powerful cacique in the Vega, [he] is not

mentioned at all and seems not to have been involved.” Since Fray Ramón Pané

was sent by Columbus to live among the people of Guarionex in 1495, it is

unlikely this would have worked very well had Columbus and Guarionex been so

hostile to each other in March 1495 (Pané 1999, xxi). It could not be ruled

out that one of the caciques subordinate to Guarionex might have been important

at Vega Real (Kulstad 2008, 39, discussing Maniocatex, more often spelled Manicaotex).

Ferdinand Columbus indicates that Caonabo, frequently

described as one of the most powerful caciques of the island, was taken alive at

the battle, along with his wives and children, e preso vivo Caunabo,

principal Cacique di tutti loro, insieme co’ suoi figliuoli, & con le sue

donne (F. Columbus, Historie, 1571, 123). It perhaps should be noted

that Keen, in translating the passage, adds a footnote stating the F. Columbus

was in error in that “Caonabó neither participated in nor was made prisoner in

this battle, but was captured by Hojeda by a ruse.” (See Tyler 1988, 164, summarizing the three most common narratives of how Caonabo was captured.)

As noted above, Deagan and Cruxent cite Martire to give the

number of Columbus’s opponents at Vega Real as 5,000. Let us look at Martire’s chronicle more

closely. He notes that Columbus had

left Hispaniola in 1494 to try to reach the Far East, which he believed to be close, but

after some exploration returned only to learn that Caonabo was besieging Alonso de Ojeda at the

blockhouse of Santo Tomás. Martire says Caonabo would not have begun such a siege had he known that Columbus himself was coming with imposing

reinforcements, no habían levantado el sitio hasta que vieron que venía el

mismo Almirante con gran escuadrón (Martire 1892, vol. 1, Decada 1,

lib. 4, cap. 1, 208; Parry and Keith 1984, vol..2, 208). Martire

says that Caonabo was encouraged by other caciques to expel the Spanish.

Caonabo then left with a large force, probably to attack Columbus, but Ojeda separated

the cacique from his men and brought him to Columbus, where he was seized

and put in irons, fué preso y encadenado (Martire, 210; Parry and Keith,

209).

Martire continues that, after the capture of Caonabo,

Columbus resolved to march throughout the whole island, determinó recorrer

las isla (Martire 1892, cap. 2, 211; Parry and Keith 1984, 209). After a

long passage concerning the Spanish search for gold in Hispaniola, Martire returns

to the events concerning Caonabo, now in irons. Martire states that Caonabo

pleaded with Columbus to protect his territory, which was being ravaged by his

native enemies in his absence. His real purpose, however, was to lay a trap for

Columbus because Caonabo’s brother had assembled five thousand men to attack

the Spanish. Ojeda, however, decided to go on the attack rather

than wait to be attacked and, finding the ground well adapted for cavalry

maneuvers, his horsemen rode down the enemy, who died if they remained in place.

Only those who abandoned their houses for the mountains and rough cliffs

survived, abandonando sus casas se refugiaron en las montañas y en ásperos

riscos (Martire 1892, cap. 4, 222; Parry and Keith 1984, 211).

This passage from Martire, which I believe ends with a

description of an encounter that was either part of the Battle of Vega Real or followed soon after, does not conform with Las Casas or F. Columbus in that Columbus

himself is not present, but it agrees with them in stating

that cavalry was essential in the victory, though dogs are not mentioned.

It may also give a clue about the type of fighting that was occurring at

this time in that the natives that awaited the battle in their houses were

killed, whereas those who fled might survive. Does this mean that some of the

“battles” described involved not an open field of battle but something closer to the

attacks of the U.S. Army against defenseless villages in the nineteenth century plains warfare? Perhaps David Traboulay (1994, 26) is correct in arguing that when Columbus, his brother Bartholomé, and Ojeda "took a series of military expeditions all over the island," they were specifically attacking villages that could not pay the tribute Columbus was imposing.

Oviedo (1851, vol. 1, lib. 3, cap. 1, 59) also describes

Caonabo’s siege of Santo Tomás, in territory under his control, which involved

assembling archers to attack the fort and burn it. Ojeda, as in Martire’s

account, captured Caonabo, but Caonabo’s brother, who was well respected by the

Indigenous (hombre de mucho esfuerço quisto de los Indios) then gathered

a force of seven thousand men, most of them archers, and began fighting to free

his brother. Oviedo also describes the

panic that men on horseback caused among the Indigenous. Ojeda received an additional three hundred

men from Bartolomé Columbus and captured Caonabo’s brother. Later, according to

Oviedo, the focus of the opposition to the Spanish shifted to Guarionex, who

was able to gather fifteen thousand men (Oviedo 1851, cap. 2, 60), whom

Bartolomé Columbus attacked in a night battle in which he captured Guarionex in

1497 (Wilson 1990, 98).

Can the Accounts of Martire and Oviedo Be Correlated with

Those of Las Casas and F. Columbus?

Samuel Wilson (1990, 90) argued that the Battle of Vega Real

“was such a rout that Martyr does not even mention it.” Martire did, however,

mention Columbus’s desire to march across the island and also described

actions conducted by Columbus’s subordinates that may well have been part of

the overall plan that probably began with the Battle of Vega Real. It is not

clear to me why Martire would not want to mention a rout, as Wilson

argues. Another possible explanation is that perhaps the initial attack of Columbus and Guacanagari and

their forces was not a battle where their enemies were engaged and soundly

defeated on a battlefield, but rather a rampage through the villages and fields

of the northern Vega Real with only gradually developing resistance from the

inhabitants. Perhaps the soldiers from

whom Las Casas and F. Columbus received their information had altered

memory in such a way as to make the encounters into a single battle of which

they could be proud, rather than a rampage that Oviedo and Martire preferred to

ignore.

Carl Sauer (1966, 88-89) takes his summary description

primarily from F. Columbus, but curiously adds, “This was no proud conquest,

nor was it called such. The easy submission was entitled ‘pacification.’” This

would be a questionable judgment if one were to focus on the accounts of Las

Casas and F. Columbus, which were described as victories against considerable odds, but it is more easily accepted if passages from Oviedo

and Martire that probably relate to the same period are allowed to add a caution

as to how confined geographically or limited temporally the battle was. It might be expected that Martire would have incorporated the account of F. Columbus, given that he knew Fernando as a boy at the royal court and probably tutored him. (Perez Fernandez and Wilson-Lee 2021, 8).

Obviously, the inability to identify a single or specific

set of leaders of the Indigenous at Vega Real makes it difficult to imagine

the battle, and the problems in correlating the accounts of Las Casas and F.

Columbus with accounts of probably the same period by Martire and Oviedo,

undermine any faith that a definitive history of the conflicts of 1495 is even

possible.

Where Did the Battle of Vega Real Occur?

Another problem concerns the location of the battle. Ferdinand Columbus says that Columbus encountered the

scattered Indian horde two days’ march from Isabela, due gionate lungi dalla

Isabella (Historie 1571, 123; Columbus and Keen 1984, 149, at least in the 1992 edition,

incorrectly translates as a ten days’ march). Las Casas says that the

Columbus’s march from La Isabela was ten leagues, diez leguas,

from La Isabela (Las Casas, vol. 2, lib. 1, cap. 104, 97).

If one is to argue that the events around a siege of Santo Tomás

described by Martire and Oviedo contain some of the circumstances that are

attributed to the Battle of Vega Real, then it is to be noted that this would require some interval for the theater of war to move south. According to the letter of Michele de Cuneo,

who was at the fortress at Santo Tomás when it was built was built, it was about 27

leagues from La Isabela and only about two leagues from where Caonabo lived

(Parry and Keith 1984, 88-92, translation of the letter).

That the Spanish would want to fight within an easy distance

of a fortress is not in doubt. Martire (Decada 1, lib. 4, cap. 2, p 212-13)

says a number of refuges, número los refugios, were added so that they

could be reached quickly in case some violence from the islanders might

threaten the Spanish, por si acaso alguna vez les amenazaba alguna violencia

de los insulares. This would indicate that having encountered hostility,

groups of Spanish men might need a place where they could shelter and perhaps

force some acceptable sense of engagement on the natives, rather than just

enduring sporadic and random attacks.

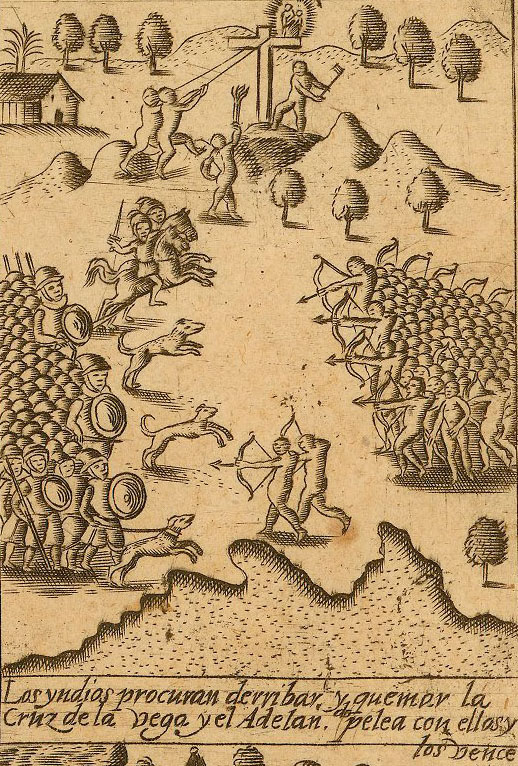

The frontispiece of Antonio de Herrera’s 1601 edition of Historia

general depicts an attempt by los yndios to destroy la Cruz de la

Vega, which is being defended by Bartolomé Colon, referred to in the

caption as el Adelantado, a title given him by his brother Christopher.

Whether this was part of the Battle of Vega Real or totally unrelated has long been

a subject of historical dispute. A particularly detailed

paper by Apolinair Tejera (1945) includes careful analysis of relevant passages

in Oviedo and Herrera, which refer to crosses erected at fortresses in

Hispaniola with little commentary. Those early accounts were expanded

novelistically, and with significant spiritual elements, by later writers.

Apolinair Tejera concluded that Herrera’s reference to

a “miracle of the Holy Cross of the Conception of La Vega” was not dated by

him, and could not be, and that the exaggerated incident of Santo Cerro must

have occurred long after the bloody disaster of Vega Real (el exajerado

incidente del Santo Cerro debió ocurrir much después del sangriento desastre de

la Vega Real). It is curious, however, that the illustrator of Herrera's book included dogs in that battle, just as he had in his depiction of the Battle of Vega Real, though the Spanish forces in the fight over the cross were under Columbus's brother, rather than Columbus. Floyd (1973) accepts

Tejera as correctly separating the incident of the cross from the Battle of

Vega Real. See Figure 3.

|

|

Figure 3. A frontispiece panel of the 1601 edition of

Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas’ Historia general (vol. 1) shows a

battle in defense of a cross. The

caption translates: The Indians try to tear down and burn the Cross of La Vega

and the Adelantado [Bartolomé Columbus] fights with them and defeats them, los

indios procuran derribar y quemar la Cruz de la Vega y el Adelantado pelea con

ellos y los vence. Some authors have argued this was part of the Battle of

Vega Real. Detail, John Carter Brown Library, JCB B601 H564h.

|

One recent researcher

(Stone 2021, 376) argues that upon reaching the plain of Vega Real,

Columbus and Guacanagari “set up a small palisade atop present-day Santo Cerro,

a mountain that overlooks the entire Cibao valley located in Guarionex’s

cacicazgo.” After a day of fighting, the Spaniards retreated to

Santo Cerro. Waking the next morning,

however, they were surprised to discover that the opposition forces had

disappeared in the night. This perspective on the battle conflicts with

accounts that the Tainos were put to

flight after the attack of the horses and dogs.

It also seems to accept that what is generally called the Battle of Vega

Real could as easily be called the Battle of Santo Cerro. Kulstad (2008, 41) notes that those who

distinguish the battles of Vega Real and Santo Cerro usually point out that

Santo Cerro was further from Isabela than Las Casas and F. Columbus would place

the battle. I do not think Stone adequately addresses this difficulty. Guitar (2001) also connects Santo Cerro to Vega Real but provides few references.

How Much Do We Know about the Battle of Vega Real?

The progression of events during 1495 was, I believe, something like the

following:

Angered by Spanish incursions into his territory and that of

other caciques, but seeing that isolated attacks against the Spanish only led

to defeats, Caonabo begins to assemble a force, which numbers 5,000 or more, to

push the Spanish back and perhaps to remove them from Hispaniola altogether. Guarionex

may have encouraged Caonabo to revolt, and may have been pulling strings to get

other caciques to cooperate with Caonabo, but he probably did not take any battle

leadership role until after 1495.

Columbus returns from his explorations of the Cuba and other

islands in 1494 and determines that threats to mining operations and Caonabo’s

gathering of an army require a coordinated response led by him. Caonabo is

captured by Ojeda, either by a ruse or in a skirmish. It is not impossible that F. Columbus appropriately connects his capture to the first major fighting in Vega Real. Ojeda takes Caonabo to La

Isabela, where he is kept in chains pending being sent back to Spain. A brother

of Caonabo gathers a large force, or supplements the force Caonabo has already assembled, now amounting to about 7,000 men dedicated to freeing Caonabo and continuing his crusade against the Spanish.

Beginning at the northern end of the plain of Vega Real, but

perhaps continuing near one of the defensive fortresses, Columbus, supported by

perhaps 3,000 men under his ally Guacanagari, uses cavalry and dogs and greatly

shocks the Indigenous inhabitants. Caonabo’s brother and other caciques are

taken prisoner at Vega Real or in subsequent actions. Columbus’s victory is followed by

additional battles and skirmishes led by Alonso de Ojeda and Bartolomé

Columbus, using portions of Columbus’s army. Some battles occur near the

defensive fortresses.

The encounter at Vega Real as presented by Las Casas and

F. Columbus and as depicted in the frontispiece of Herrera’s Historia

general of 1601, was a classic European battle. Although a great number of Indigenous people

had gathered at Vega Real, they may not have been organized as an army prepared

for battle but rather have been more of an intertribal gathering, assembled

to air their grievances and reach a consensus on what to do about the Spanish. They were, in any case, unprepared to respond to the organized force that began to move through them and their villages before they could even understand what

they were facing. Guacanagari would have understood that the forces of Caonabo

or his brother were not expecting what Columbus was about to deliver, and he

could have calculated how to support Columbus, making his army a significant

part of the blow that Columbus landed at Vega Real. He was assuring his own survival and probably seeking the best treatment possible for his people.

Columbus was determined to pacify the island, but he is only

mentioned as participating in the first battle that occurred after he entered

the Vega Real. He could have easily returned to La Isabela after his initial

victory and left the mopping up to Alonso de Ojeda and his brother, which

explains what Martire and Oviedo were describing. The entire island was not pacified, but the

area under Caonabo’s control probably was. Guarionex was able to mount significant resistance in 1497 (Wilson 1990,

75, 78), but was also defeated and had to flee. Columbus would have continued

to enjoy the support of Guacanagari but may have by then also incorporated some

remnants of the forces of other defeated caciques as well.

Does this perspective of the battle alter any of my findings

or opinions with regard to the use of dogs at Vega Real? Probably not. The dogs could have been chasing people who were already panic-stricken and might have

had to bite them more at the side than at the front to bring them down. The

dogs might be less apt to encounter weapons from people who were fleeing rather

than going into battle, and the dogs may not have been as easily hit by arrows

since they would not have been moving before a backdrop of armed Spaniards. They would have been just as useful in these

circumstances.

I do invite comments to this blog and particularly references to additional sources. Should you not wish to comment publicly, please email me at jensminger@msn.com.

References

Anderson-Córdova, K. F. (2017). Surviving Spanish

conquest: Indian fight, flight, and cultural transformation in Hispaniola and

Puerto Rico. The University of Alabama Press.

Columbus, F. [Fernando Colombo] (1671). Historie de S.D. Fernando Colombo: Nelle quali s'ha particolare, & vera relatione della vits, & de' fatti dell' Ammiraglio D. Christophero Colombo. Venice: Appresso Francesco de' Fraceschi Sanese.

Columbus, F., & Keen, B. (1992). The life of the admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son Ferdinand. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

de Cuneo, M. (1893). Lettera. Savona, 15-28 ottobre 1495. In

Raccolta di documenti e study pubblicati dalla R. Commissione colombiana,

pel quarto centenario dalla scoperta dell’ America (Vol. 2, p. 99).

Ministero della pubblica istruxione, 1892-96.

Deagan, K. A., & Cruxent, J. M. (2002). Columbus’s

outpost among the Taínos: Spain and America at La Isabela, 1493-1498. Yale

University Press.

Denevan, Wi. (1996). Carl Sauer and Native American

Population Size. Latin American Geography, 86(3), 385–397. Figueredo, A. (1978). The Virgin Islands as an Historical

Frontier Between the Tainos and the Caribs. Revista/Review Interamericana,

8(3), 393–399.

Ensminger, J. (2022). From hunters to hell hounds: the dogs of Columbus and transformations of the human-canine relationship in the early Spanish Caribbean. Colonial Latin American Review, 31(3), 354-380.

Figueredo, A. (1978). The Virgin Islands as an historical frontier between the Tainos and the Caribs. Revista/Review Interamericana, 8(3), 393-399.

Floyd, T. S. (1973). The Columbus dynasty in the

Caribbean, 1492-1526 (1st ed.). University of New Mexico Press.

Friede, J., & Keen, B. (Eds.). (1971). Bartolomé de

las Casas in history: Toward an understanding of the man and his work.

Northern Illinois University Press.

Glazier, S. (n.d.). Trade and Warfare in Protohistoric

Trinidad. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress for the Study

of Pre-Columbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles (pp. 279–283). Centre de

Recherches Caraibes.

Guitar, L. (2001). What really happened at Santo Cerro? Origin of the legend of the Virgin de las Mercedes. Caribbean Amerindian Centrelink, Feb. 18. http://indigenouscaribbean.files.wordpress.com/2008/05/guitarsantocerro.pdf.

Heiser, C. B. (1973). Seed to civilization: The story of

man’s food. W. H. Freeman.

Herrera y Tordesillas, A. de. (1601). Historia general de

los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del mar Oceano

(Vol. 1–4). Imprenta de la Real Academia de la Historia.

Hervella, M., San-Juan-Nó, A., Aldasoro-Zabala, A.,

Mariezkurrena, K., Altuna, J., & de-la-Rua, C. (2022). The domestic dog

that lived ∼17,000 years ago in the Lower Magdalenian of Erralla

site (Basque Country): A radiometric and genetic analysis. Journal of

Archaeological Science: Reports, 46, 103706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103706

Hoffecker, J. F., V.V. Pitulko, & E.Y. Pavlova. (2022).

Beringia and the Settlement of the Western Hemisphere. Bulletin of the St.

Petersburg Department of History, 67(1).

Inigo Abbad y Lasierra. (1866). Historia Geografica,

Civil y Natural. Imprenta y Libreria de Acosta.

Jennings, F. (1975). The invasion of America: Indians,

colonialism, and the cant of conquest. Published for the Institute of Early

American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press.

Jennings, F. (1976). The invasion of America: Indians,

colonialism, and the cant of conquest. Norton.

Kroeber, A. L. (1934). Native American Population. American

Anthropologist, 36(1), 1–25.

Kulstad, P. (2008). Concepcion de la Vega 1495-1564: a preliminary look at lifeways in the Americas' first boom town. M.A. thesis, University of Florida.

Kulstad González, P. (2020). Hispaniola—Hell or home?:

Decolonizing grand narratives about intercultural interactions at Concepción de

la Vega (1494-1564). Sidestone Press.

Las Casas, Bartolomé de. 1875–1876. Historia de las Indias. 5 vols. Madrid: Miguel Ginesta.

Martire d’Anghiera, P. (1892). Fuentes históricos sobre

Colón y América (Vol. 1). Imprenta de la S.E. de San Francisco de Sales.

Morison, S.E. (1942). Admiral of the ocean sea: a life of Christopher Columbus. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Morison, S. E. (1963). Journals and Other Documents on

the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. The Heritage Press.

Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo Fernández de. 1851–1855. Historia general y natural de las Indias

[1535]. 4 vols. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia.

Pané, F. R. (1999). An Account of the Antiquities of the

Indians. Duke University Press.

Parry, J. H., & Keith, R. G. (Eds.). (1984). New

iberian world: A documentary history of the discovery and settlement of Latin

America to the early 17th century (1st ed, Vol. 2). Times Books : Hector

& Rose.

Perez Fernandez, Jose Maria, and Wilson-Lee, Edward (2021). Hernando Colon's New World of Books: Toward a Cartography of Knowledge. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rosenblat, A. (1967). La Poblacion de America en 1492:

Viejos y nuevos calculos. Colegio de Mexico.

Sauer, C. O. (1966). The Early Spanish Main.

Cambridge University Press.

Stone, E. W. (2021). The Conquest of Española as a

“Structure of Conjuncture.” Ethnohistory, 68(3), 363–383.

Sued Badillo, J. (Ed.). (2007). General history of the

Caribbean. Volume I, Autochthonous societies. Palgrave Macmillan : UNESCO

Pub.

Tejera, A. (n.d.). La Cruz del Santo Cerro and the Battle of

Vega Real. Boletin Del Archivo General de La Nacion (Santa Dominga), 8(40–41),

101–119.

Tinker, Ti., & Freeland, M. (2008). Thief, Slave Trader,

Murderer: Christopher Columbus and Caribbean Population Decline. Wicazo Sa

Review, 23(1).

Traboulay, David M. (1994). Columbus and Las Casas: The Conquest and Christianization of America, 1492-1566. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

Tyler, S. L. (1988). Two worlds: The Indian encounter

with the European, 1492-1509. University of Utah Press.

Wilson, S. (1997). Surviving European Conquest in the Caribbean.

Revista de Arqueologia Americana, 12, 141–160.

Wilson, S. M. (1990). Hispaniola: Caribbean chiefdoms in

the age of Columbus. University of Alabama Press.

.jpg)